A while ago I had my musical ears retooled by overhearing some modern women’s music, as will, hopefully, be addressed later in these pages. One of the many disruptive effects of this was an inability to hear older music as I used to hear it; I’d hear hesitancy, falseness, bombast in works whose imperfections I used to be okay with because I knew no better. Of course, the works that still stood up were the works I had never questioned before – Forever Changes, Hatful of Hollow, Unknown Pleasures, etc, but, every time, I had to hear them anew to understand how they worked in this new world. And, of course, what I really wanted to hear was more women’s voices in this music.

When Casablanca Moon came on the playlist I instantly recognised it as one of these works. I’ve always liked it of course, but without properly seeing it as the stand-alone masterpiece it is – competing with its follow-up Desperate Straights and the Faustian preview of itself that’s Acnalbasac Noom has been a hard gig.

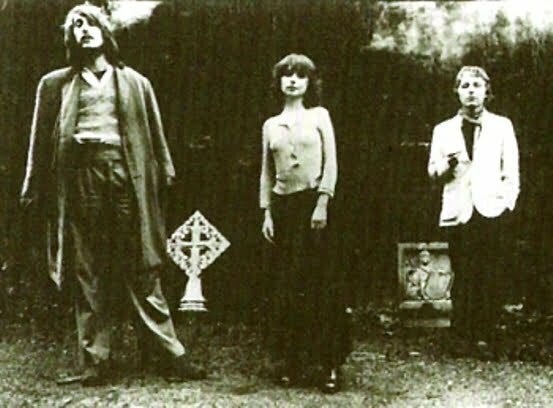

Casablanca Moon is a collection of witty art songs, full of clever concepts, sophisticated rhymes, and smart musical turns, of the sort Cole Porter used to write, in an occasionally Latin-tinged rock and pop idiom, splendiferously orchestrated by Roger Wootton of the English prog-folk act Comus. The songs are written by Anthony Moore (a Brit) and Peter Blegvad (an American) and sung by Dagmar Krause (a German). Put in print, that sounds unbearable, but this gang makes magic happen. And maybe that’s the key to understanding Slapp Happy, to see them as a gang of three, not the ad hoc and initially clumsy commercial arrangement they stumbled into when Polydor grew tired of A. Moore’s solo field recordings (only the bravest critic would have predicted that the gauche outfit who wrote and performed on the debut LP Sort Of Slapp Happy could progress to greatness), nor the left-of-field pop act that Virgin Records tried and failed to groom with this recording.

It’s the story of three loners who found each other in the international art-and-intrigue hub that was 1960/70s Hamburg; Dagmar singing cabaret in the Reeperbahn since 1964 and recording various German projects (most noticeably, the avant garde second side of the 1970 I. D. Company LP split with Ingar Rumpf, which resembles her post-Slapp Happy work), Moore with his experimental Polydor deal, Blegvad with his odd linguistic obsessions. It’s the tightness and familiarity of this team behind the scenes, away from the music, that gives their music its poise and intimacy; there’s a Jules et Jim, distinctly European quality of true friendship between men and women (Krause and Moore would marry, while Blegvad’s girlfriend gave Slapp Happy their name) that makes their music profoundly sexy where it could easily have been silly, Krause singing about the characters that her friends have invented for her as if they were, or could have been, her lost lovers, the man who was “Half Way There”, the endangered spy in the title track, “Me and Parvati”, the sole female character, who has the singer (or, in another reading, is the singer) “sobbing with lust” in Paris France – oddly, the spiritual home of this record to a listener on the other side of the world, explained by its arrangement of elements; some potent French words (visage, cortège, and a quote from Rimbaud), albeit sung with a German accent, a Beat poet’s familiarity with Hindu and Japanese culture, occasional Latin rhythms, familiarity with the literary conventions of poetry and the spy novel, all in the perfect proportions to evoke a monde of Bohemian salons linked by trains and steamers rather than jets. The mystery of its “Frenchness” has a further, simpler explanation – French artists of this period simply weren’t writing songs in English or trying to make a mark in Britain. The Germans were, but Slapp Happy sound far less German than Faust, Can, or Amon Duul II.

This is a record that wears its scholarship very lightly indeed - a song about “Michelangelo” packs as much verismo detail into 3 stanzas as you’ll ever need, but skips along jauntily enough to be the theme for a children’s show. The double tracking of Krause’s distinctive alto warble in places gives her voice softness but also, being out-of-phase, an auto-tune like penetration, the concentrated sound of many voices. It shouldn’t work; on her later, more political recordings this same voice can well be described as daunting, but here it’s the voice of a fantasy European girlfriend, inducting the listener into her culture before, too good to be true, she disappears and leaves you to it, reappearing a few years later as the diehard communist who denounces you for the bourgeoise frivolity of loving her.

But it doesn’t end there of course, nor is, as is so often the case, our story better off left at such a point. Dagmar Krause stayed on with Henry Cow after Slapp Happy’s recording of Desperate Straights with their backing, then recorded several albums of very varied tone with other Henry Cow alumni as The Art Bears, as well as collections of Kurt Weil and Hanns Eisner songs, and sang on Here and There, the flip side of the Stranglers’ 1984 single Skin Deep.

Peter Blegvad has gone on to record and produce a series of unclassifiable cultural artifacts, including the serialized comic strip Leviathan and a song covered by Leo Sayer. Anthony Moore even had a payday of sorts, when asked to write the lyrics for two popular post-Roger Waters Pink Floyd albums. Slapp Happy got back together a few times, toured and recorded other albums, and in 1991 Blegvad and Moore wrote a really-quite-good opera for Krause to sing the lead in (Camera, which was broadcast on TV in Germany and the UK). And on YouTube you will find a video of the trio, nearing 70, singing and playing the songs from Casablanca Moon in 2018, showing the same skill, cohesion and aplomb they had in the 1970’s - three lives well-lived through Art.

Next algorithmic suggestion: - Wolf City, by Amon Duul II.

hey "sort of" is great!