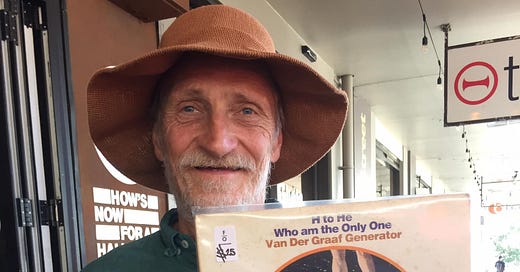

When Hayley gave me a little birthday money to spend at Flying Out, I didn’t really expect to find a score like this in the second hand bin. $25 worth of music I first heard when I was 15; what would it sound like today? It sounds bloody good. H to He Who Am The Only One was Van Der Graaf Generator’s second album, and I can’t better Tim Bowness’s description of the (possibly even better) sequel, Pawn Hearts – “45 minutes of Gothic, haunted house atmospherics and beautiful song fragments beaten into submission by lunatic, dissonant riffing”. Van Der Graff Generator are a classic example of undersung heroes. With a unique sound which seems to have influenced everyone that mattered in the realm of serious electric music in Britain, they had no hits or successes to speak of (except in Italy), yet continue to be respected (and, they keep on playing today as a trio). VDGG never sold out, but never really cashed in on not selling out either.

You can hear their influence on Roxy Music, David Bowie*, Split Enz (compare “The Emperor In His War Room” with any Phil Judd song on Mental Notes), The Cure and of course John Lydon’s bands – when Johnny Rotten, as he was then known, was first given the chance to front his own radio show he played two tracks from Peter Hammill’s solo album Nadir’s Big Chance (1975), which is VDGG as a punk band before there were such things as UK punk bands**.

Phil Oakey and Jim Kerr are fans and Luke Haines wrote a song about Peter Hammill called “Peter Hammill”. VDGG have also got to be down there somewhere among the roots of Dark Metal and Electronica, because there’s something more authentically dark, scary and fantastic in Hammill’s lyrical vision than existed before, because the mathrock complexity of some of the riffing adds to its power rather than embroidering it as the fiddly bits of other prog acts tended to do, because a lot of Hammill’s singing style involves screaming in tune, and because experimental sections of electronically treated weirdness are crucial to the mood.

Where did this all come from? I really have no idea. Hammill’s interviews are no help, except for this line: “Incidentally I was never much good at copying or covering anyone else and almost from the very beginning played and sang my own stuff.” VDGG were inspired by jazz and blues, and US acid rock, and instrumentally by the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, but how they arrived at this weird, dark and heavy sound is a mystery to me, although it’s surely relevant that Black Sabbath probably had many of the same influences***. Heavier, darker, weirder – that was the genius loci of Britain entering the 1970’s. The destruction of The Beatles, Syd Barrett, Brian Jones, Jimi, and Joe Orton; the country’s fall into debt; R.D. Laing, Don’t Look Now, Colin Wilson’s occult books and the witchcraft revival; the rise of serial killers, terrorists and kidnappers - downers for the post-acid comedown.

One of the themes of these essays is, what produces originality in electric music? Originality, as distinct from novelty, being the projection of a distinct new type of musical personality, and the creation of an actual or potential influence fertile enough to become the origin of further sounds. Not the only pathway, but one of the best, is a combination of the inability to do the expected or desired thing, combined with the unquenchable urge to prevail, and an openness to the sound of new combinations****. Peter Hammill could have been content to cover blues songs badly until he became as proficient at it as Hugh Laurie. Or, having developed his distinct style of song, he could have remained conservative in its instrumental accompaniment, and rejected collaboration with atonalists and the generators of electronic noise. Instead, he sensed, or trusted, or accepted out of desperation and loneliness, that this wild environment would cover his deficiencies, expand his emotions, and inspire him onwards. And, the more experimentalist members of the group accepted that the fragments of conventional beauty in songs like the sublime “A House With No Door” should be made even more beautiful. Choices involving indifference to purity of genre, commercial chances, and the expected groupings or uses of instruments. Van Der Graaf Generator had no guitarist, except for the occasional (one solo per album) borrowing of the magician Robert Fripp from King Crimson.

So much for the intensity of the music, but the intensity of Hammill’s songs is also critical to the effect. His lyrics are open confessions of his fear of loneliness and death. He’s not afraid to scream “I love you!” even though the object of his love is never defined in any way. When he projects these feelings into fantasies, as is often the case, words like “doom” appear. “Pioneers Over C” is about the horrors of interstellar flight; it starts with a nod to Pink Floyd’s “Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun” (a rare case where I can pin-point a contemporary inspiration), but ends up more like Sam Neill in Event Horizon. “Killer”, the first track on H to He (Charisma wanted to put “Killer” out as a single, which would have been cool, but the band vetoed this as a “sell-out”) is about the darkest fish in the ocean:

All the other fishes fear you…

In a black day, in a black month

At the black bottom of the sea

Your mother gave birth to you

And died immediately

Because you can’t have two killers

Living in the same pad

And when your mother knew that her time had come

She was really rather glad

Death in the sea, death in the sea

Somebody please come and help me, come and help me

Fishes can't fly, fishes can't fly

Fishes can't and neither can I

now I'm really rather like you

For I've killed all the love I ever had

By not doing all I ought to

And by leaving my mind coming bad

And I too am a killer

For emotion runs as deep as flesh

Yes and I too am so lonely

And I wish that I could forget

Few singers have been brave enough to compare themselves to such a monster, few have even imagined such a thing. And Hammill’s not doing it in a macho way; there’s no masculine boast in his intent, this mother was as terrifying as her child (there’s pity for her, but there should be for him), and his vulnerability always underlies his ability to scare us. Pity and terror – the elements of tragedy, as defined by Aristotle, are the elements of Hammill’s muse, reinforced by the complete avoidance of humour. It’s the lush, fertile bed that Van Der Graaf Generator’s music supplies that makes this vision something other than bleak. It’s all just so good, so beautiful, and so powerful that the human spirit can find in it the strength to survive its condition, and brood another day.

* Acknowledging that there’s no public acknowledgement by these first two. How could one band be so influential? The market for weird, progressive music in Britain was undersupplied in 1970. Today, if you like an act, you can usually find 100 copies of it pretty quickly. In 1970, the opposite was true – if you liked an act you saw live, you were lucky if you could find an LP by one act like it that was well-recorded. You’d listen the heck out of that one disc. And, the competition between the bands wasn’t desperate; they all toured together on the student circuit.

** It was Ricky Nadir, not Richard Hell, who inspired “Johnny Rotten” and “Sid Vicious”.

*** What is “War Pigs” if not the lowbrow equivalent of “The Emperor In His War Room”? And what opera might be their highbrow companion?

****The astute reader will recall my Adlerian notes in the last essay.

Algorithmic suggestion : You’re A Stranger To Me Now by i. e. crazy

yeah I have Nadir and a couple of others of Peter's as well as most of their stuff on vinyl and cd( was a great cd reissue series a few years back.) Killer though was my "entry"

was my first VDGG albumn, then Pawn Hearts. As you say, it was difficult to find these in the 70's.