Jealousy is perhaps the most involuntary of all strong emotions. It steals consciousness, it lies deeper than thought. It is always there, like a blackness in the eye, it discolours the world.

― Iris Murdoch, The Sea, the Sea

It's extraordinary how potent cheap music is.

— Noel Coward, Private Lives

Once upon a time I worked my way through a list of songs receiving creative NZ funding, but the results were so dispiriting I never tried again. Everyone knows that if you want to make Art in New Zealand you don’t apply to Creative NZ, you apply to Work and Income. So once again, I’m grateful to William Dart on New Horizons, this time for checking out some recent recipients of the Government grant, because his ears were caught by the opening bars of ‘Jealous’ by Jaz Paterson (feat. Phodiso), and so were mine.

The underwater filters, the tensely cycling motif (an objective correlative for the emotion), the busy dance beats that pull against it - all this reminds me of Amaarae’s Fountain Baby, one of my favourite 2023, but discovered this year, albums. That a New Zealander cares about such music (or has found a similar spot in their own art without knowing about it) gets my respect right away. Thus, I’ve sought out the rest of Paterson’s work and found myself liking it a lot more than I expected. Her forte is New Zealand-made A-pop that’s as modern in its style as anything in the US charts, emotionally sincere songs with a crystalline specificity, a sense of place and time in each lyric that’s unusual today.

Unlike too much Kiwi pop, Jaz’s music and lyrical themes are nocturnal - ‘Liquid Adrenaline’ begins at 3am - and uneasy; the spirit of her home city, Christchurch, though within this cosmopolitan sound it could apply to any city, as in her dream of ‘LA’ from 2021’s Ache EP.

If you’re cold, as Jaz is in ‘Lonely’, one way to keep warm is by dancing, which, if you’re an electronic musician, is also a way to stay connected to the future. There are a handful of dance collaborations in Jaz Patterson’s small resume, my favorites being those with kiwi duo Sly Chaos (Conor Till, Michael Enderby). Again, we’re in a rhythmically complex world, again, we’re caught up in its propulsive flow, and again, Jaz’s singing is perfection, mannerism held in check so that emotion itself can soar.

I’ve recently taken to using YouTube Music’s algorithmic playlist function, trained by years of our household picks, as a form of sortilege, like reading the tea-leaves. I guess this puts me on the slippery slope to AI-generated content, but this app is becoming, pardon my pun, a smart cookie. After ‘Liquid Adrenaline’, the algorithm chose Jockstrap’s ‘Concrete over Water’, which takes Paterson’s idea of the uneasy city-scape into a surreal prog-folk electronica.

And after ‘What am I meant to do’, the app chose Lorde’s ‘Royals’, the massive, voice-of-a-generation diss track that broke Lorde, an acknowledged inspiration to Jaz, into the market she dissed, perhaps the very song that first detached Paterson from her indie-rock and folksy beginnings and onto the beguiling and shifting terrain of electronica.

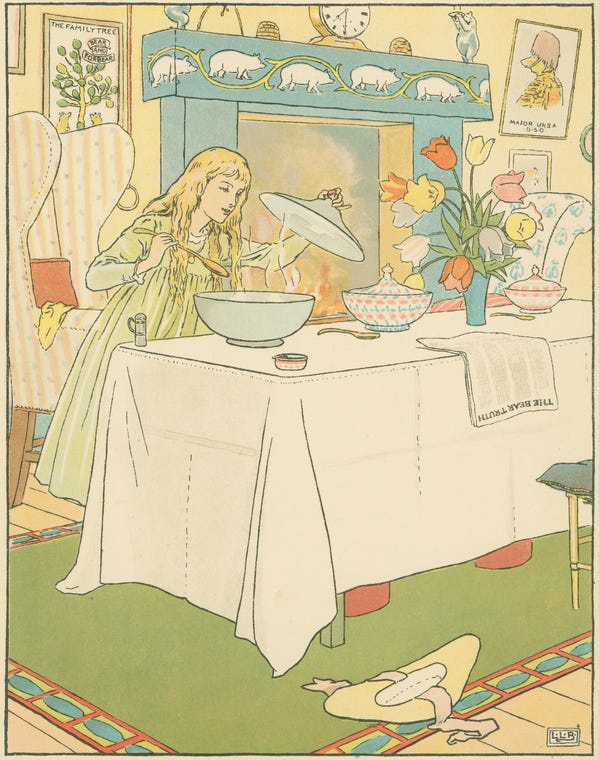

We don’t hear much about Goldilocks these days, despite there being innumerable adaptations of Red Riding Hood, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, Puss in Boots, Hansel and Gretel, and the others. But the Goldilocks archetype does seem relevant here, Jaz Paterson sneaking into the big Bearhouse of A-pop and testing, and instinctively finding, the just-rightness of every element within it. We’ve had three new songs in the past few weeks, all of them good, varied, yet produced (by Dan Martin) with an ear for consistency - hopefully this means an album, or at least a substantial mixtape, is on the horizon.

*********************************************************************************

Prof. Mathew Bannister has published a fascinating article in the Women & Music Journal, ‘Folkie Madonnas and Founding Fathers - Women and Authenticity in 1960s–1970s Folk Rock” on the critical reception of female folk singers in the 1960-70s, and the criteria by which authenticity was judged by the influential (mostly male) East Coast critics of the day, by whom they were

”…marginalized… in the emergent critical discourse of rock music… through considerations of authenticity central to the developing rock aesthetic. This aesthetic was based around a white-constructed figuration of Black sound, a white, masculinist conception of rock and roll as loud, exciting, youth-oriented rhythmic music derived primarily from Black rhythm and blues (as these critics argued had been the case with 1950s rock and roll).”

That a concept that might glibly be called “cultural appropriation” now was held to define authenticity in the past seems ironic, and made me think about how authenticity itself has been redefined and revalued in my lifetime. When I was researching the 2000 Lash album The Beautiful and The Damned a few posts back I came across a YouTube comment to the effect that "just because Lash were well-produced, people thought they were manufactured" and realized that even punks don't think like that so much anymore, that the public is more understanding of collaboration between artists and technologists, and we don't need völkische reminders that an artist is "real" anymore, do we?1

It’s a fascinating article - Matthew, who’s able to write a scholarly paper without too much indulgence in academic jargon and grandstanding citation of anachronistic sources, and who has an artist’s desire to entertain as well as inform, has read and summarized a great deal of the criticism surrounding the music of rock’s glory days, a time when the hardest-working critics assumed rock-star status and had loyal fans waiting for their every opinion.

”Recurring critical themes include accusations of mainstream commercialism, using implicitly gendered terminology typical of mass culture critique, with “pop” qualities implicitly opposed to rock authenticity.”

Do we still feel this way, now there’s a genre for everything?

Very relevant to modern pop, Bannister describes how

”Greil Marcus critiqued the genre’s focus on “sensitive personal confession” as solipsistic. Bangs termed singer-songwriters “I-rock” and characterized them as “relentlessly, involutedly egocentric.” In both musical and lyrical terms, they argued, singer-songwriters represented apolitical individualism.”

I would argue that there is truth in their criticism, but that it rests on larger truths - the Logos vs Eros division (greater masculine interest in order and status vs greater feminine interest in personal connections), and, insofar as it might be applied to modern trends, on the increasingly atomized experience of the individual within society, whose political activity is thus increasingly spurious and non-communal, so that solipsism today contains enough universality to be the basis of many a communal experience.2 Besides, it’s been many years since the emo bands brought solipsism fully into the masculine rock canon.

Ironically, perhaps, I find this description of the “approved” style from Dave Marsh, the villain of Bannister’s piece from its intersectional “heuristic of suspicion” perspective, to be a perfect summary of much of the women’s music I admire today, if we modernize its “[R&B]” to include trap, rap, house, reggaeton, and other dance rhythms of, or influenced by, the western hemisphere’s African diaspora:3

“artistically and commercially viable pop music based on an [R&B] rhythmic process”.4

This definition would seem to include, for instance, such transcendent recent works as ‘Diet Pepsi’ by Addison Rae, ‘Easy’ by Le Sserafim, ‘Sociopathic Dance Queen’ by Amaarae, ‘Mic Check’ by Sophie Hunter, and ‘Liquid Adrenaline’ by Jaz Paterson. Describing those works more specifically, perhaps, than it describes the work of the best-respected modern guitar bands, male or otherwise, who, for the most part, seem less immediately connected to those “R&B'“ rhythmic processes.

Authenticity, if I were to define it today, is no longer a stylistic matter; but a personal quality, an intolerance of falsehood, a commitment to one’s music (and its proper audience should an artist be lucky enough to find one) that overrides the commercial or moral or critical values of anyone but the artist and the (now equally authentic) listener.

Algorithmic destination - ‘Party in the USA’ by Miley Cyrus

The “gutbucket” singing that connoted authenticity in white blues performance circa 1970 is rarely heard today.

The exaggeratedly atomized experience of a solo electronica singer contributes to the charm of that genre

Dave Marsh may have fetishized the electric guitar, who hasn’t, but as he didn’t imagine synthesizers and sequencers and autotune we don’t need to qualify his text to include them.

Or, as Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau wrote in 1972’s It’s Too Late to Stop Now , “rock and roll has to be body music”.