Neither the torture chamber nor the disco knows about the existence of each other. But there is psychic contact between the two; the evil doings on the disco floor have their counterpart in the dungeon below.

~ Bruce Bickford

People with courage and character always seem sinister to the rest.

~ Hermann Hesse

My career has been, year after year, waiting to be disposed of.

~ Frank Zappa

I was probably 14 or so when my mum called out to me from the dining room, which was also the room where she conducted all her mum business, the room with a phone and a radio, “listen to this weird music! It sounds like something you might like.” I’m not sure what she was comparing it to, but it sure was weird, a minimal, repetitive, layered, jokey, freestyle .and technologically inventive recording with the unforgettable title of ‘Help I’m A Rock’.

A few years later, when I got a job that paid enough to buy LPs and met a few people with common interests and more advanced tastes, I found ‘Help I’m A Rock’ on Freak Out!, the first (double) LP by a rough-looking group excitingly called Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and later I’d come to appreciate its influence on Soft Machine (‘We Did It Again’) and Can (‘Vitamin C’). There were other exciting songs on Freak Out!, like ‘Trouble Every Day’ and “why Don’tcha Do Me Right’ (which I later heard covered by Auckland punk band Terrorways) and at various times up to the mid-70s I owned most of Zappa’s albums (including Lumpy Gravy, the 1967 avant garde LP which only had a few seconds of pop music). The first three Mothers of Invention albums are at their heart great garage-psych albums, Zappa is copping his pop pastiches from the (relatively, for him) limited palate of the electric blues, garage, folk-rock and pop styles of the American mid-60’s, and the best part of his satire from the emerging dichotomy of the freak vs straight worlds, so there’s still some sense of artistic unity. Zappa’s riff for ‘Trouble Every Day’, underlying a scathing commentary on the Watts Riots of 1965, restyles Howling Wolf’s ‘Smokestack Lightening’ into a go-go beat, and this was the song Verve producer Tom Wilson heard when he signed the band.

Listen to these lyrics - this isn’t “For What It’s Worth” - I can’t think of any other rock star with a major label contract prepared to tell the truth like Zappa does here, impartially calling out structural injustice, racist violence, pointless destruction, and media exploitation. If there’s been anything like this since, we weren’t allowed to hear it. And Frank was just getting started.

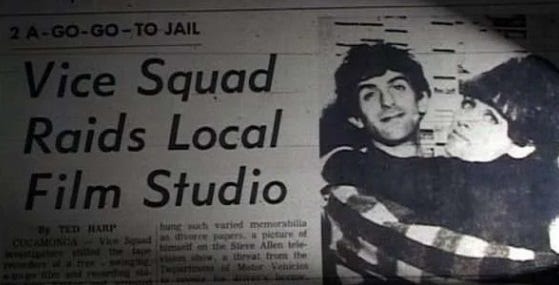

Wilson is the greatest producer you’re still allowed not to know about, and a “best of” his work would include early albums from Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground, Nico, Soft Machine, Sun Ra, and Eric Burdon and the Animals, as well as Simon and Garfunkel, for whom he created the epic soundscape that’s ‘The Sounds of Silence’ (1964), inventing the folk-rock sound. But for the most part, Wilson wasn’t a producer’s producer so much as an artist’s producer, generously relinquishing aesthetic control to anyone as full of ideas as Frank Zappa (or, for that matter, Lou Reed and John Cale). The Mothers’ 3rd LP, We’re Only In It For The Money, the first produced by Zappa, is one of the few real masterpieces of 1967 music, up there with The Piper At The Gates of Dawn. It’s also in places very much a hyperpop album, due to Zappa’s maximalist approach to overdubs and electronic effects and his rapid-fire edits including analogue glitching ideas, like the insertion of a “dust on the needle” scratch, that are digitally replicated today. And (beginning with ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’ on Absolutely Free) he’s learned to blur the line between satire and pornography, much as William S. Burroughs did, both to advance his liberal social agenda and revenge himself on the authorities who, in 1965, had busted and put out of business the studio he ran and sentenced him to 6 months in prison (ten days served) for making a sexy tape with a female friend at the behest of an undercover cop, who had initially requested a film (“conspiracy to commit pornography”). That friend, Lorraine Belcher’s entertaining account of that session is given here. The local paper reported that

"Vice Squad investigators stilled the tape recorders of a free-swinging, a-go-go film and recording studio here Friday and arrested a self-styled movie producer." - that Zappa made movies (he had composed and recorded two soundtracks for low-budget films) was a misunderstanding the same newspaper itself had created with an earlier headline referring to him as a “movie ‘Mogul’”, which had brough him to the attention of the Police.

Critics have accused Zappa’s music of lacking emotional depth, which I think is fair (it’s also said about Bartok, so he’s in good company), but surely hate’s an emotion, and We’re Only In It For The Money, with an emotional palate that switches rapidly from scorn to pathos, can feel like it’s swimming in empathy.

However, I found it hard to love much of of the music Frank was releasing by the mid-70’s. The default garage-punk-psych sound of the early Mothers was replaced by a modern jazz-funk sound, with time signatures that only the GTO’s could dance to, that still makes me queasy (jazz died with Dolphy, Ayler and Coltrane, and you can quote me on that). I do have fond memories of listening to Apostrophe’ and One Size Fits All when my teenage friends and I discovered marijuana, full as these albums are of cool synth effects, fabulous guitar solos, touches of grandeur, and New Wave dynamics (Frank, who never used drugs, made some of the best stoner music) but Zappa’s humour seemed to get cruder and more scatological, and the singing more objectionable, around the time I was trying to find a more sophisticated way of expressing my own self.

In my Rasputina article I discussed how the formation of gender at adolescence can edit one’s playlist - music too feminine may not have suited me as a growing boy, but a little later, when sex itself became a distant possibility, I didn’t want to be caught listening to anything as crudely masculine as some of Frank’s 70’s material either (in the same way, I was never an AC/DC fan). Kevin Ayers, Syd Barrett, Robert Wyatt were the soft, sophisticated models of heterosexuality I preferred, following Bolan and Bowie. How do we become who we are? In our teens, by eclipsing our anima and suppressing our shadow and, only much later, by learning from them, works in progress. So my relationship with Frank Zappa, the greatest polymath and most assured composer of the rock era, has remained in a sort of embarrassed limbo for decades.

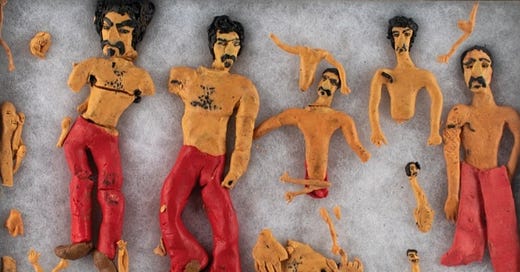

Then last week Hayley, not then a Zappa fan, suggested we watch a film she’d heard about on the internet called Prometheus Garden (1988), allegedly scored by Zappa, and made in claymation style by animator Bruce Bickford. At the beginning of Prometheus Garden you’ll see a warning that the film contains “much graphic violence, viewer discretion advised”, which might well strike you as funny, but the gore sequences are in fact hard to watch even knowing everything is made from clay and being shaped by hand every fraction of a second. The claim that the soundtrack is by Zappa seems to be false, it’s somewhat similar to but more consistent than his compositional style, but as we’ll see the two did collaborate - there’s a close affinity between their world-views, and some telling differences - but the 1988 film was made after their period of close collaboration ended. The vision of Prometheus Garden is best described as lysergic, at quite a high dosage. A vision of heaven and hell in 28 minutes of fluid transformation, which took years to make. Prometheus Garden, like Bickford’s other works, seems to me to embody what Freud called polymorphous perversity, “…the amorphous and changeable nature of the libido prior to being shaped in the processes of socialization and psycho-sexual development” as purely as any artwork made by an adult can. Bickford’s own childhood wasn’t happy and his model-making gave him escapist enjoyment and a place to experience and experiment with the will to power stifled in his relationship with his parents, whereas the first real harm done to Zappa’s ego was his run-in with the law, a trauma easy, and fair enough, for him to politicize.

I don’t recommend watching Prometheus Garden on hallucinogens, but I do recommend watching it carefully if you’re considering using hallucinogens.

Bickford’s work has one occasional motif, the disco to dungeon pipeline, and the disco is called CASL, but by the time he made CASL, his most technically perfect version of the idea, he’d decided that discos were passe, so in that film CASL is presented as an art museum instead.

Bickford bonded with Zappa in 1971 after seeing Zappa’s film 200 Motels, and the two collaborated on several projects, the largest being Baby Snakes, a video accompaniment of a live album. As with Prometheus Garden, it’s as if Bickford’s showing us some dark, but not despairing, underlying truth about human nature as he plays with his characters.

Hayley loved the title track from Baby Snakes, a short Rorschach blot of a song that ends in a wonderfully Scriabin-esque chord. so I tracked down the studio version, on the 1980 album Sheik Yerbouti, and it turned out that this was the Zappa album I needed to hear. Recorded 1978-79, it’s full of New Wave energy, and the punk pastiche ‘Tryin’ To Grow A Chin’ is allowed the kind of artistic unity that ‘Why Don’tcha Do Me Right' had, as its put-upon 14 year old protagonist sings:

I wanna be dead

In bed

please kill me

'Cause that would thrill me

It’s also full of smut, track 1 being ‘I’m In You Again’, a sexually explicit R&B parody of the sentiment of Peter Frampton’s 70’s hit ‘I’m In You’. Zappa’s R&B on Sheik Yerbouti is pared back, with none of his jazz-rock excesses, and these songs could, and probably should, be reworked with trap beats today, feat. Jessie Reyez. There’s ‘Flakes’, where guitarist Adrian Belew turns out a perfect Bob Dylan parody, basically Frank having a grump about lazy, rip-off tradespeople hiding behind their union rules. ‘Jewish Princess’ aroused the outrage of the Antidefamation League, a US anti-antisemitism watchdog, but Zappa failed to back down, saying “The ADL is a noisemaking organization that tries to apply pressure on people in order to manufacture a stereotype of Jews that suits their idea of a good time. They go around saying that other people are saying things that produce stereotype images of Jews.”

The winner though, and the track voted Zappa’s most problematic song of all time, is ‘Bobby Brown (Goes Down)’. In it, Zappa seems to predict the Crisis of Masculinity we hear about today, mocking conservative’s fears about what’s going to happen to men once feminists take away their entitlements over women; and maybe he’s predicting, as in ‘Trouble Every Day’, that the results aren’t going to be any prettier than the causes.

Bobby Brown’s story starts,

I got a cheerleader here wants to help with my paper

I'll let her do all the work 'n' maybe later I'll rape her

But then

Women's Liberation

Came creepin' all across the nation

I tell you people, I was not ready

When I fucked this dyke by the name of Freddie

She made a little speech then,

Aw, she tried to make me say when

She had my balls in a vice, but she left my dick

I guess it's still hooked on, but now it shoots too quick

Until, after a few more adventures, which I’m leaving out here purely in the hope you’ll play the song,

Oh God, Oh God, I'm so fantastic!

Thanks to Freddie, I'm a sexual spastic

And my name is Bobby Brown

Watch me now, I'm going down

Why is Zappa wearing middle-eastern garb on this 1980 release? Why is it called Sheik Yerbouti? For much the same reason that the Clash later wrote ‘Rock The Casbah’; the Islamic theocracies, beginning with Iran’s revolution, were banning Western music, including rock, and in the case of Saudi Arabia, all public musical performance after the al-Jamaa al-Salafiya al-Muhtasiba movement seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca in 1979. Thus the album, Zappa’s first release as a truly independent artist, is a fuck-you to the repressive forces in American culture, on the rise at that time, with its radio-friendly sound and boundary-testing lyrics. One might say that he was trying to get cancelled - ‘Bobby Brown’ was banned by some radio stations, but he’d done what he could.

Zappa’s great opportunity to defend freedom of expression in the abstract arose in 1985, after Tipper Gore, wife of the conservative Democratic senator Al Gore, bought a copy of Prince’s Purple Rain soundtrack LP for the couple’s 11-year old daughter, and was scandalized by the song ‘Darling Nicky’.

I knew a girl named Nikki

I guess you could say she was a sex fiend

I met her in a hotel lobby

Masturbating with a magazine

The fear that Prince’s pantomime naughtiness might lead the younger Gore astray, which led the Gores and others to form the Parents Music Resource Center (PRMC) lobby group and protest against smut and violence in popular song, or as they called it “Porn Rock”, isn’t on the face of it ridiculous; music has life-changing powers, and Prince’s was then revolutionary and his vision and its properties poorly understood. But that song’s about female autonomy, and Wendy and Lisa who played in his band The Revolution were also role models to girls watching Purple Rain, like poet Maggie Nelson, who revisited her preteen experience of ‘Darling Nikki’ in the New Yorker in 2015.

”I recited “Darling Nikki” for two years like a prayer. Then, there was high school. The “Purple Rain” moment had passed, but I am here going to credit any good sex that happened over the next few years to Prince. He was so many things besides a sex symbol for suburban white girls like me, so please forgive me my momentary narrowness. I’m just struggling to give my thanks. I imbibed it then without naming it, but I can see now how important it was that his feminism and queerness and blackness all blazed together, implicit, a streak of insistence on what’s possible, a rejection of the paltry ways of being that pretend to be all that’s on offer.”

But Nelson’s memoir was far in the future when Frank Zappa turned up on Capitol Hill to defend the right of musicians to free expression, in the company of only two other artists, John Denver, a born-again Christian whose ‘Rocky Mountain High’ had been caught out by an anti-drug song blacklist, and Dee Snider of Twisted Sister. You can theorize all you want about the harmful effects of Twisted Sister’s music, but the harmful effect of the PRMC’s publicity was real enough for 12-year old Hayley, then a member of the Sick Motherfucking Friends Of Twisted Sister fan club, whose parents broke in half and threw out her LP of ‘Stay Hungry’ - its torn cover still holds a place of pride in our record collection.

The music industry didn’t send anyone to defend its interests, because it wanted these same politicians to support a tax on blank tapes (in a few more decades the industry’s forever corrupt and short-sighted version of self-interest would see to it that the major record companies weren’t willing to develop their own streaming models until it was too late). Sen. Paula Hawkins (R-Fl) made the claim that things had gone downhill since Elvis sang (she didn’t quote lyrics like “I’m like a one-eyed cat, peepin’ in a sea-food store” from ‘Shake Rattle and Roll’, his 1956 cover of a song that was already a 1954 radio hit for Big Joe Turner (on the R&B chart) and Bill Haley and his Comets (on the pop chart)). Anthony L Fisher’s gave this account of the session for Business Insider in 2020:

”Zappa said the PMRC's complete list of demands "reads like an instruction manual for some sinister kind of toilet-training program to house-break all composers and performers because of the lyrics of a few."

He took dead aim at the inherent conflict of interest in senators hosting a group comprising their wives while debating "a tax bill that is so ridiculous the only way to sneak it through is to keep the public's mind on something else: 'Porn rock.'"

When Czechoslovakia was finally freed from the yoke of Communist oppression in 1989, Frank Zappa was invited to play at the Prague celebration (the other invitee was Lou Reed). Czechoslovakia’s most important underground band in the communist era was called The Plastic People of the Universe, whose name was a reference to a song on Absolutely Free. Members of this band, founded in 1968, as well as their fans and supporters, were frequently jailed, beaten, and sometimes deported simply for trying to play in forbidden styles. What does this have to do with Zappa’s indulgence in and defense of Porn Rock?

That’s a complicated argument indeed, but I’d like you to consider two of the literary works which underlie our Western distaste for authoritarianism. Have you read 1984? The only revolution Winston Smith gets up to, or wants to be involved in, is a sexual revolution, and the book charts his course from fantasies of violence against women, through an encounter with a prostitute, to a chance at sexual love, freely shared.1 Or take The Trial, Franz Kafka’s story of an ordinary man condemned under inscrutable laws, which turns out to be, for the most part, the record of K.’s flirtations with different women; this, not his unwanted struggle with the Law, is the meaning of the life K. has to lose.2

Who am I to disagree with the experts?

Zappa suggested to the PRMC hearing that information about the moral content of records could be given by printing the lyrics on the cover, which is true but interferes with artistic expression in another way. The eventual compromise the industry agreed to was the Parental Advisory sticker. Goodhart’s law states that “"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure", and the measure of the Parental Advisory sticker is usually “profanity”. So that any artist can earn the sticker (and thus make their work look more grown up and desirable) with a single “fuck”. It’s an imperfect measure, because profanity itself has no definable relation to meaning.

There hasn’t yet been a celebrity Frank Zappa tribute album like the modern collections of songs by Marc Bolan, Yoko Ono or Adam Green, and he hasn’t turned up as a nostalgia act or a movie or TV song yet that I know of, surprising given his creativity and his continued popularity. It’s almost as if his songs are too strong, and their interpretation too challenging, for our “safety art'“ times. In 2021, toward the end of peak cancel culture, Lily Moayeri wrote a defense of Zappa for the Rock and Roll Globe which begins

”I became a Frank Zappa fan in 2020. This happened instantly after watching the documentary ZAPPA, 27 years after his death in 1993, 54 years after the release of his first album in 1966.

What won me over were Zappa’s strong stands and beliefs—not to mention his steadfast drug-free policy—delivered with mic drop timeless quotes articulated with honesty.”3

I recommend watching Prometheus Garden, Baby Snakes as well as the 2020 documentary ZAPPA. because the visual record of Zappa’s world is an insight into his character that helps to appreciate more of his music, however too much it seems.

Algorithmic Advisory - ‘CVNT’ by Sophie Hunter

George Orwell was an admirer of Henry Miller, and Miller’s books were usually banned for their explicit sexual encounters, presented as Miller’s path to enlightenment or spiritual revolt

”Here in my opinion is the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English-speaking races for some years past. Even if that is objected to as an overstatement, it will probably be admitted that Miller is a writer out of the ordinary, worth more than a single glance; and after all, he is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses.” - George Orwell, Inside The Whale, 1940

I thought Orson Welles’ 1962 adaptation of The Trial had exaggerated the “sex'“ aspect of the story until I reread the book.

From the Zappa Wiki:

”Zappa instructed his fans to read Kafka's short story "In the Penal Colony" (German: "In der Strafkolonie") before they listened to the track The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny on We're Only In It For The Money.

Nigey Lennon claimed on page 63 of her book: Being Frank - My Time With Frank Zappa: "Out of a strange reluctance to appear intellectual, Zappa pretended that he never read anything he didn't absolutely have to read, but one of the first long conversations we had on the tour was about Franz Kafka. Frank seemed to be thoroughly familiar with everything Kafka had ever written, even obscure things like "A Country Doctor"."

I think Moayeri goes too far in labelling the GTO’s as a “girl group”, their album Permanent Damage is mostly unlistenable and at its best not as good as what the Manson Girls were capable of.