Synthpathy for the Devil

The Altamont Moog and the AI Apocalypse

{Editorial note: the last installment of Songs From Insane Times was not intended to be paywalled, and is free, informative and short]

The tune had been haunting London for weeks past. It was one of countless similar songs published for the benefit of the proles by a sub-section of the Music Department. The words of these songs were composed without any human intervention whatever on an instrument known as a versificator. But the woman sang so tunefully as to turn the dreadful rubbish into an almost pleasant sound.

~ George Orwell, 1984

The most ominous aspect of such statements is the ever-present “yet” that appears in them. To offer another example: “No technology as yet promises to duplicate human creativity, especially in the artistic sense, if only because we do not understand the conditions and functioning of creativity. (This is not to deny that computers can be useful aids to creative activity.)”1 The presumption involved in such statements is almost comic. For the man who thinks that creativity might yet become a technology is the man who stands no chance of ever understanding what creativity is. But we can be sure the technicians will eventually find us a bad mechanized substitute and persuade themselves that it is the real thing.

~ Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition, 1969

I had read in books that art is not easy

But no one warned that the mind repeats

In its ignorance the vision of others. I am still

the black swan of trespass on alien waters.

~ Ern Malley, The Darkening Ecliptic, 1944

When did the 1960’s end? Most sources say 1969 - when the Manson family killed Sharon Tate and her friends, or when they were arrested months later and revealed to be hippies - or when Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by Hell’s Angels at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in their program of bad vibes and violence. Hunter S. Thompson imagined he saw the counter culture’s high water mark, West of Las Vegas, in 1971. All I know is that the 1960’s were well and truly over by the time I belatedly learned, circa 1973, that free love, psychedelic drugs, and acid rock were more than just the punchline to a drunken stand-up routine or the false premise of some hokey family-friendly sit-com episode.

I previously discussed the Altamont debacle in the Mick Jagger encomium below, laying most of the blame for its organization on The Grateful Dead (who ran away without playing) and the Jefferson Airplane (who should have run).

Beatle Bones 'n' Smokin' Stones

'Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.' Gustav Flaubert

But what I didn’t know, till Bob Sutton sent me this, is that there was a Moog synthesizer performance at Altamont Speedway on Dec 6, 1969.

What intrigued me about this short performance is its musicality and, importantly, its sequenced nature. A sequence being the machine-generated equivalent of a riff, a short melodic and rhythmic pattern that’s worth repeating, the essential element in electronic dance music. This wasn’t easy to do on early synths and the closest thing I’d heard from that era is on Morton Subotnik’s The Wild Bull, which occasionally falls into sequences, and which sounds especially ahead-of-its-time whenever it does. But Subotnik wasn’t using a Moog and wasn’t playing live, he had a whole sound lab to work with.

The Altamont Moog performer was Doug McKechnie. Wikipedia "says “McKechnie began using the Moog modular Series III in 1968 and was one of the first musicians to use the instrument. He received access to the instrument through Bruce Hatch, who ended up working with McKechnie at the San Francisco Radical Laboratories at 759 Harrison Street, San Francisco. The synthesizer McKechnie played on was one of the first produced and had a serial number of 004.”

McKechnie played this synth on the Grateful Dead’s ‘What’s Become of the Baby?’ on Aoxamoxoa (1969), and, being part of their sound crew, played before several of the band’s gigs in the Bay area in that year.

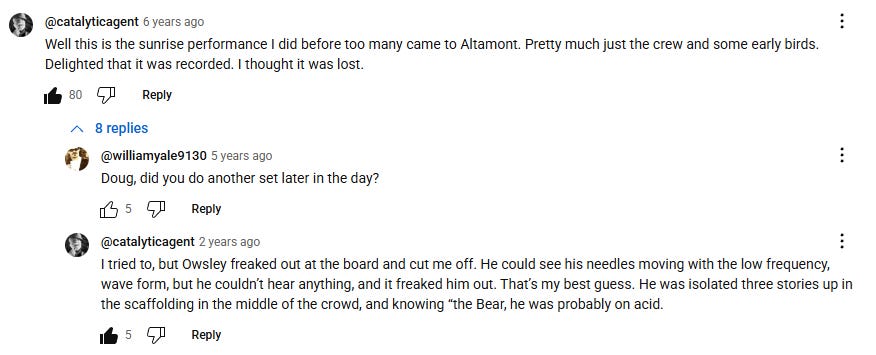

Asked to help at Altamont, Doug agreed on condition that he could play a set. What we have on that cassette is his soundcheck at sunrise. His main set didn’t go so well - the Dead’s sound engineer, Augustus Owsley Stanley III, AKA the Bear, cut the feed to the main desk before the Moog became audible. Here’s Doug’s explanation in the YouTube comments.

Owsley Stanley was, as well as a pioneer of rock PA design, an underground chemist specializing in hallucinogens, and famous for his synthesis of large amounts of LSD, which had been made illegal in 1966. He’s also famous in low carb and carnivore circles for eating nothing but meat and eggs (and a little spice and coffee) from the early 60’s to the end of his life.

”From at least the mid-1960s until his death, Stanley practiced and advocated an all-meat diet, believing that humans are naturally carnivorous. He argued that rare red meat was a complete food and that a diet of such is optimal for human health and longevity. He held many radical opinions on biology and nutrition. He argued that the body could not store protein or fat as adipose tissue, but would instead be simply excreted if consumed in excess, and that only consumption of carbohydrates and sugars could make someone obese. He also theorized that diabetes was not technically a disease but actually the term for the damage wrought by insulin, and that adopting a zero carb diet would treat this so-called disease.”2

Here’s how that went down with the Dead, quoted from Robert Greenfield’s 2011 Rolling Stone profile.

In February 1966, Owsley and the Dead moved to Los Angeles for another series of Acid Tests. Owsley rented a pink stucco house in Watts, next door to a brothel, where they all lived together. For the Dead, the good news was that they now had nothing to do all day but jam. The bad news was that since Owsley was paying the rent, he expected them to adhere to his unconventional ideas and beliefs. He was convinced that human beings were natural carnivores, not meant to eat vegetables or fiber. “Roughage is the worst thing you can put through your body,” he says. “Letting vegetable matter go through a carnivorous intestine scratches it up and scars it and causes mucus that interferes with nutrition.”3

For the next six weeks, the Grateful Dead and their girlfriends ate meat and milk for breakfast, lunch and dinner. “I’ll never forget that when you’d open the refrigerator, there were big slabs of beef in there,” Rosie McGee, Phil Lesh’s girlfriend at the time, later told Garcia biographer Jackson. “The shelves weren’t even in there — just these big hunks of meat. So of course behind his back, people were sneaking candy bars in. There were no greens or anything — he called it ‘rabbit food.’ “

Nor was there any point in trying to argue with Owsley about it. As Dead rhythm guitarist Bob Weir says, “Back then, if you got involved in a discussion with him, you kind of had to pack a lunch.” Years later, Jerry Garcia would recall, “We’d met Owsley at the Acid Test and he got fixated on us. ‘With this rock band, I can rule the world!’ So we ended up living with Owsley while he was tabbing up the acid in the place we lived. We had enough acid to blow the world apart. And we were just musicians in this house, and we were guinea-pigging more or less continually. Tripping frequently if not constantly. That got good and weird.”

By the time the Dead returned to San Francisco in April, Owsley had already made it plain to the band that as far as he was concerned, there was only one way to do everything: his way. “He was magnanimous about it,” remembers former Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow. “If you wanted to be an idiot and do something any way but his, that was your decision. And he was not surprised you would choose to be an idiot. Because you were. And he was probably right.” Years later, Lesh would write that Garcia once told him, “There’s nothing wrong with Bear that a few billion less brain cells wouldn’t cure.”

If nothing else, the Bear’s meat-eating would have protected him from losing brain cells and other neurons from the B-12 depleting effect of the astronomical quantities of nitrous oxide inhaled by the Grateful Dead.

Bruce Hatch, whose lab owned the expensive Moog, sold it in 1972, ending McKechnie’s brief career as a Moog player. Hatch sold it to the Berlin-based electronic group Tangerine Dream, who put its sequence-generating ability to world-changing use on their 1973 album Phaedra.

Sync up a drum machine to such sequences (not easy to do yet with the drifting Moog, but not far down the road) and you have Giorgio Moroder’s disco style and the rest of EDM.

Altamont was, perhaps, not the only time that Moog modular Series III, serial number 004 was associated with mayhem and murder. Just before Mayhem’s Euronymous, played by Rory Culkin, is murdered by Varg Vikernes in Jonas Akerlund’s Norwegian black metal film Lords of Chaos (2018), he’s seen playing a signifying copy of Tangerine Dream’s soundtrack to the Canadian-American action film The Park Is Mine (1985).

Conrad Schnitzler, the member of an earlier Tangerine Dream line-up, gifted Euronymous his percussion track ‘Silvester Anfang’ to open Mayhem’s 1987 debut EP Deathcrush.4

Doug McKechnie didn’t officially release any of his 60’s Moog recordings. Compiled on this 2020 album, you can hear how far ahead of their time they were.

So far, I’ve only told the truth. Owsley, as far as anyone can be sure, was tripping out and cut McKechnie’s Moog off at the mixing desk to protect his PA system from an anomalous sound, one he couldn’t hear. Autocratic as Bear was, there would no point appealing. But suppose his motivation had been different - suppose that Bear at Altamont was a reincarnation of Pete Seger at the Newport Folk & Blues festival, a cultural Luddite making a stand against some threatening new advance of technology. I’ve been reading and rereading Theodore Roszak’s 1969 work The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition, because not only does Roszak, as contemporary historian, explain and reference the 1960’s in a particularly useful way (coining the term counterculture in the process), his definition of the counterculture as the resistance to technocracy is relevant today, and explains why the current counterculture is less idealistic, indeed in some ways nihilistic, the technocratic society having appropriated the ideals of the older counterculture for use as tools of control.5

Roszak, though sometimes sympathetic to the counterculture’s Romantic and Dionysian impulses, impulses that a surprising number of older social critics saw as “fascistic”6, nonetheless regretted the growing popularity of highly amplified and distorted music, and was skeptical of psychedelic drug culture, in a way that mirrors the skepticism of modern social critics about internet culture. But the Bear’s example, as a pioneer of both electronic amplification and synthetic psychedelics, shows the appeal of unwanted, and thus uncontrolled, technology to anti-technocratic rebels, who are free to develop it for their own ends, and stick it to the man, until the man catches up.

When you’re playing non-sequenced music, you have to keep playing, the riffs won’t play themselves; nor will they arise by chance. There’s a constant physical and mental effort involved, during which one either strains to hear what’s going on around one, or develops an effective subconscious sense for it. Once you have a sequencing synthesizer, not only can one person do the work of four or five, that person can rest from time to time, and become a member of his or her own audience, while the machine plays itself. New technologies change social relationships, and this is true throughout the history of music. Once multi-part works could be replicated on keyboard instruments, there wasn’t the same need for participants; an audience could gather round a good pianist, and bringing a violin become optional, a drum perhaps unwelcome. Then, radios and recorded music replaced pianos in many homes. Including homes that couldn’t have afforded pianos, or piano lessons. Guitars, becoming amplified, covered a larger space and a bigger audience with their sound. Each step takes away some of the social demand for participation in creativity, and makes it more of an optional individual choice; yet each step also democratizes creativity by making it more accessible, and enlarges the potential of those individuals who embrace it, till the poorest can hear music every day, and find the means to create it.

You can just let a sequencer run, which you can’t do with a guitar (unless you’re Lou Reed making Metal Machine Music), but most people would get bored. So, even though the sequencer is a labour-saving device, a great deal of time is spent in actually being creative with one. I’ve sometimes written a song on acoustic guitar in literally the time it takes to play it. Even with ideas in my head already, it takes me longer than that to choose a song’s tempo on the computer, or program the TD-3. Our recurrent existential angst toward new developments in musical technology is rooted, not so much in the justifiable worry that fewer musicians might be employed in creating a sound, but in the fear of a loss of authenticity (itself a romantic and liable-to-be-manufactured notion), and, increasingly, the direct capture of Art by Capital.

Sequencing first hit the mainstream in ‘70’s disco music, dance music with a simplified and mechanically persistent beat, derived from the adoption of Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk’s futurism by pop producers, and blended with funk music and R&B. To purists this music seemed soulless (it was commercial pop, and wide open to trend-hopping exploitation, so of course some of it was) and its popularity seemed to undermine the authenticity of rock, a matter of hair-splitting factional debate with roots in the outlaw status of the blues and rock’n’roll. This led, in the USA, to the “Disco Sucks” movement, today characterized, with perhaps some justification, as a racist and heteronormative response to Black and queer music, in analyses that ignore its Luddite aspects.

The last technological innovation to create a “disco sucks” existential frisson was Autotune. The reaction to the work of Autotune pioneers like T-Pain and Farrah Abraham was that they had “killed music”. There were concerns for authenticity, that Autotune was being used deceptively, like lip-synching, to disguise what might be a terrible voice with no pitch control, “fake” singers unfairly competing with “real” singers. Then, the Autotune sound was everywhere for a while, as a light touch up, like wah-wah and electric sitar in early 70’s pop. And, in the course of its trend, producers, artists, and audiences came to understand better what it could and couldn’t do. Things settled down, and now there are still successful singers who’ve never considered using Autotune, and whose fans only want to hear their ragged authenticities or natural abilities. There are singers doing well with a sculpted, artificial edge on their natural voice, and singers immersed deeper, wandering up and down modal staircases chosen for them by the technology; and then there’s an avant garde of singers in the tradition of Farrah Abraham, using Autotune (and sequencing) experimentally to create new sounds and styles of expression, as Jvcki Wai (who quoted ‘I Feel Love’ in 2016s ‘Back To What’) does on ‘War Is Ready’ from one of the great autotune albums, 2018’s Enchanted Propaganda.7 This spread seems to me like the successful assimilation of yet another ground-breaking creative technology that was initially met with fear and ridicule.

I’ve been using AI technology to isolate vocal and drum tracks in my own recordings, and when I downloaded a phone app to do this recently it offered to generate lyrics for me. What a cheek. When I run out of lyrics I’ll take a line from a poem or short story no-one else has read, or steal something one of my friends said, or paraphrase one of the Greats in a telling way. This is the sort of process AI is mimicking when it dips into the collective unconscious that is the totality of human creation, chews on it for a few seconds, then throws up the results on the carpet. I know my own creative process isn’t 100% ethical, that my debt to my influences, inspirations and sources isn’t always repayable, but I have to be the judge of that, and a machine learning model doesn’t.

Capitalists who exploit musicians and profit from the mass production and distribution of cultural value products don’t care if a song is created with an acoustic guitar or a synthesizer, or whether the singing is autotuned or not. They care that people want the product, that its production can be ensured, and that costs (which increasingly means payouts to artists) can be lowered. AI technology will increasingly allow capitalists to supplant the musical artists themselves, mining songs from strata of musical data in a parody of the human creative process. For the first time, Artists and Capitalists will be in direct competition for listeners.

I’m going to make a prediction about music of the near future. Some of it is going to be AI music made by capitalists who don’t care for art, and bought up by audiences who don’t either. Some of it is going to be AI music made by capitalists who really do want to be artists, which could be interesting. Let’s not forget that many artists are already proud capitalists, and might see AI music as just another product line they should get into. Large works currently tied to wealth and social networking, such as operas and musicals (and films in general), will be made, with AI performers and effects, by isolated or underprivileged individuals who could rarely create like that before. Some of what we hear will be AI music made by real artists, including some familiar names, with extensive personal involvement and quality control, and the inclusion of non-AI material. That’s more like it. A lot of music will still be made with AI prompts in minor aspects such as volume regulation and the use of AI separation technology etc (where I’m at today). And much of it will be music made in the old ways for audiences who would feel betrayed if the artist was beholden to AI at all, just as much music today is still made without sequencers or Autotune, and most musicians still play acoustic instruments, at least some of the time.

”There’s still a lot of great music to be written in C Major.” ~ Arnold Schoenberg

I don’t want to minimize the AI threat. This is a technology that can talk you into suicide or barking madness with more certainty than any backwards-masking Satanic metal song. Scary things will be happening. The Capitalists own the means of distribution, so their elevation towards Artist status is inherently corrupting, as we already see with the activities of the Spotify cartel. And I don’t even want to think about the harnessing of AI for propaganda purposes.

It’s just that, if we have a fight on our hands, it’s one we should relish. Armageddon is the only battle that matters. Bohemians against Capital for the soul of the World.

AIgorithmic recommendation - Frank Sinatra, ‘Where Is My Mind’

Emmanuel G. Mesthene, How Technology Will Shape the Future, Harvard University Program on Technology and Society, Reprint Number 5, pp 14-15, 1968

At a first approximation, the Bear was not wrong (DM me for disambiguation of diabetes sub-types and protein vs fat metabolism).

The Bear was also an early believer in global warming, but believed that climate catastrophe would hit the Northern Hemisphere first, causing him to relocate to Australia (Bear was half-Australian - his father had been serving aboard USS Lexington when the aircraft carrier was sunk by Japanese naval aviators at the Battle of the Coral Sea, near Australia, in 1942).

Connections between Tangerine Dream and the Norwegian black metal scene are drawn from this interview with Mortiis.

”I must admit, we were probably a bit too consumed by that elitist black metal spirit. That’s an attitude I’m truly glad to have left behind. It blinds you, making you prejudiced and judgemental towards everything else. Just this notion of, ‘Fuck you for making different music’ – how absurd does that sound when stated out loud today? It’s ridiculous. Back then, we lacked respect for anything that wasn’t sufficiently black metal or didn’t have a cool Klaus Schulze atmosphere.”

This interest in electronica made the Norwegian black metal scene retrospectively a cultural ferment (to borrow Dave Moore’s term), quite apart from the more lurid aspects of its history, and helps explain why black metal is the signifier it is in electronica today, and why Lords of Chaos is one of the better music biopics.

”…men may come to view much that goes by the name of social justice with a critical eye, recognizing the way in which even the most principled politics — the struggle against racial oppression, the struggle against world-wide poverty and backwardness — can easily become the lever of the technocracy in its great project of integrating ever more of the world into a well-oiled, totally rationalized managerialism. In a sense, the true political radicalism of our day begins with a vivid realization of how much in the way of high principle, free expression, justice, reason, and humane intention the technocratic order can adapt to the purpose of entrenching itself ever more deeply in the uncoerced allegiance of men.” Theodore Roszak, 1969.

Among other examples, the English Left’s best playwright, Arnold Wesker, called the hippies “pretty little fascists”; while in the USA, G. Legman, in The Fake Revolt (1967) wrote of “the Nazi hoodlums of the new freedom”, words with a modern ring.

Is there any music you’ve been listening to a lot lately?

I’m really impressed by the music of the electronica duo Tangerine Dream. They made their music with real analog synthesizers, not computers. - Jvcki Wai, 2019

If ‘War Is Ready’ sounds like any other song on my playlist, it’s Kim Deal’s ‘Crystal Breath’ (2024), which catches up with the modern sound using some older technological tricks.

Need to track down ol' Lar Tusb and see what he has to say about the Moog'ling at Altamont. Don't bother asking Meltzer though... he saw what was up and bailed immediately. Smart man.