The support band played the kind of weird punk/funk fusion that comes from existing in a cultural vacuum. They weren’t very good, but made up for it with youthful enthusiasm.

~ Dominic Hoey, Iceland (2017)

Iceland is a deeply musical novel and a fit subject for a future blog, but, for now, what Hoey is getting at with his imaginary gig review is the need for editing, whether to arrive at a genre sound or indeed one’s own recognizable signature. If you’re drawing from a small pool of musicians, such as you might find in a small town (Hamilton, in Hoey’s book), you’re likely to end up in a band with mis-matched tastes who can’t agree on a tonal palate. And, wonders of creativity, sometimes this works and results in something fresh (I’m thinking of the first Opposite Sex line-up and LP here). Genres must evolve, and unthinkable combinations might become the new normal. If you play accordion in a metal band you simply don’t have metal anymore, but then one day someone invented pirate metal and the accordionist was in (pirate metal will never be the new normal, touch wood, but it is a thing). Or, once punk metalheads included scratching and breakbeat rhythms, and baseball caps worn backwards, and wore shorts, like the most un-metal fools on earth, there was the beginning of nu metal. There are no real rules except, there must be rules. There is no real limit except, there has to be a limit. I can hold no truck with music that does everything, that spills everywhere.

Know thyself. That’s why Black Sabbath were so definitive - they didn’t just find the new aesthetic, musically and sartorially, they ring-fenced it, trademarked it, protected it from the winds of jazz and good-time music for long enough for it to take solid form. Some wiseacre on twitter had to point out that Ozzy didn’t write the songs or play the instruments, so wasn’t as important as the others. Right. But it would have been easy to find a singer who’d cover those powerful riffs in bluesy bombast, as was the “heavy” style of the day. Ozzy’s voice, instead, was a plaintive whine that constantly questioned his own pain. As with his contemporary Robert Plant, there was something feminine about his singing, and performance, because there’s something feminine in the character of the shaman, and it’s the shamanistic aspect of Ozzy’s performance that makes him a giant, and the consistency of Butler, Iommi and Ward’s music that makes Ozzy’s pantomime weird and magical rather than, or as well as, risible. All magic is risible until the spell takes, but Black Sabbath’s spell took us long ago. You can find dozens of successful and well-rewarded guitar acts thriving on the sounds the Sabs created, but Ozzy’s influence went wider. The last time I thought of Ozzy Osborne in his lifetime, I was listening to Lil Bo Weep’s ‘Throw Down Your Fears’. Sensing a crumb of familiarity in her phrasing, it struck me that her plaintive, almost folkish voice is finding its tone and its mode, and reaching for its imagery the way it does, only because that’s how Ozzy did it.1

I’m thinking about genre again after reading the latest New Zealand entry in the 33&1/3 series, Michael Brown’s BUY NOW, an account of the 2012 vaporwave album by Eyeliner which became one of the genre’s defining works. Brown’s story, once I picked it up, became such an engaging tale of intellectual adventure, and such a generalisable introduction to internet music creation, that I decided not to listen to BUY NOW at all until I’d finished it. But twice during that first read Luke Rowell’s work, which I’d been unaware of before reading BUY NOW, did in fact get heard. Though I hardly ever listen to the radio, when I did Princess Chelsea played disasteradio’s sweet synth pop idyl ‘Aftertouch’ on RNZ in her recent interview with Tony Stamp, a must-listen for anyone interested in my subject today, and later BFM played a live version of Princess Chelsea’s own cover of ‘Aftertouch’.

If it wasn’t for synchronicity, I often think, this blog would be a poorer place.

’Aftertouch’ is a loving recreation of 90’s synthpop, its model might be Air’s ‘Sexy Boy’ (1998), though it’s probably a better song. It’s not strictly vaporwave, so what is? In what we call “world music”, places are defined by instruments. The koto sounds Japanese, the tabla Indian, the kimbali African. Music-making technology is cosmopolitan in ethos, globalist in distribution, providing much the same sound choices world-wide; the places digital and analogue electronic sounds can best conjure and define are time-stamped territories in cyberspace, and their combinations can create fresh genres, genres which may have little reach outside cyberspace in their original forms, yet can blow up on the internet.

The internet is the cosmopolitan space that transcends all identities. There is, potentially, more distance between me and a netizen who’s spent formative years gaming, a space I’ve seldom entered, than there is, online, created by supposed real world divides. Yet much of that distance can be covered, when what Michael Brown calls “the musical accompaniments of software”, e.g. gaming soundtrack effects and instruments, become a feature of internet music. Just as world music can give us aspirational citizenship of countries we’ll never visit, internet music can acquaint us with the feelings of cyberspaces lost in time or otherwise apart from our own lives.

With Eyeliner’s BUY NOW Luke Rowell set himself the goal of creating art from some especially unlikely elements. Eyeliner’s rhythm section is comprised, pretty much exclusively, of slap bass patches, mainly that used for Seinfeld’s theme and incidental music, and the Linndrum, the electronic drum kit popular in the 1980’s (Joy Division used it, but I always think of the Eastenders theme). The synths and presets are predominantly those used for early video game soundtracks. These sounds are corny to modern ears, because they were over-used commercially by people with poor taste, but they became so overused precisely because of their impact, their novelty, their special essence, and Eyeliner’s project is to revalue them by letting them inspire new compositions that embed their nostalgic power, where the laughs they might elicit are not the whole point. As Brown explains, and this thesis is a key part of his narrative, footnoted with all the relevant blog links (rather than references to long-dead theorists of not-music, the bane of the increasingly academicized 33&1/3 series), Eyeliner’s music is post-ironic.

The simplest form of irony is to pretend to find pleasure in that which displeases us, satisfaction in that which dissatisfies us. It is, thus, a way of protecting our feelings, of getting one over on fate. Deeper forms of irony, like dramatic irony and Socratic irony, are a way of protecting the feelings of others, and are useful to communicate complex ideas without giving offense. As Iris Murdoch says in The Black Prince, "We may attempt to attain truth through irony. . . . Irony is a form of tact“.2 The post-ironic artist is aware of and sympathetic to the ironic reading of their work but is pushing past it to some more important meaning, including sincerity, a meaning that includes irony but is not restricted to it.

Eyeliner’s relationship to irony can be demonstrated with comparisons - here’s ‘Toy Dog’, the album’s first track, an oddball mechanical reggae thing.

Its instrumentation closely resembles that chosen, more or less unironically, by Yoko Ono for the intro to ‘I Love All Of Me’ on Starpeace (1986).3

And here’s ‘Sneakers For Men’, Rowell’s pastiche of new jack swing, a late ‘80’s hip hop style that was commercially successful, unlike that awful ‘80’s synth rock meets 1940’s swing fusion music that was supposed to be the future in Xanadu (1980).

Several of Eyeliner’s instrumental compositions, for all their baked-in hokey qualities, have a wistful R&B-tinged melodicism that reminds me of Microdisney, always a compliment at Songs From Insane Times, and here’s Microdisney’s own pastiche of new jack swing, ‘Send Herman Home’ from 39 Minutes (1988).

‘Send Herman Home’ is a fierce satire against (I think) neo-Nazi mercenaries, and its use of a new jack swing funk style is ironic (which is not to say that the band didn’t love playing it). The jackboot tap breakdown is an ironic nod to the ‘40’s swing pretentions of the style (what else was happening in the 1940’s?). Note how closely the band’s “real” instrument choices resemble the Linndrum, slap bass, and synth presets on Eyeliner’s digitally programmed version (both versions merely approximating the “proper” instrumentation for this genre).

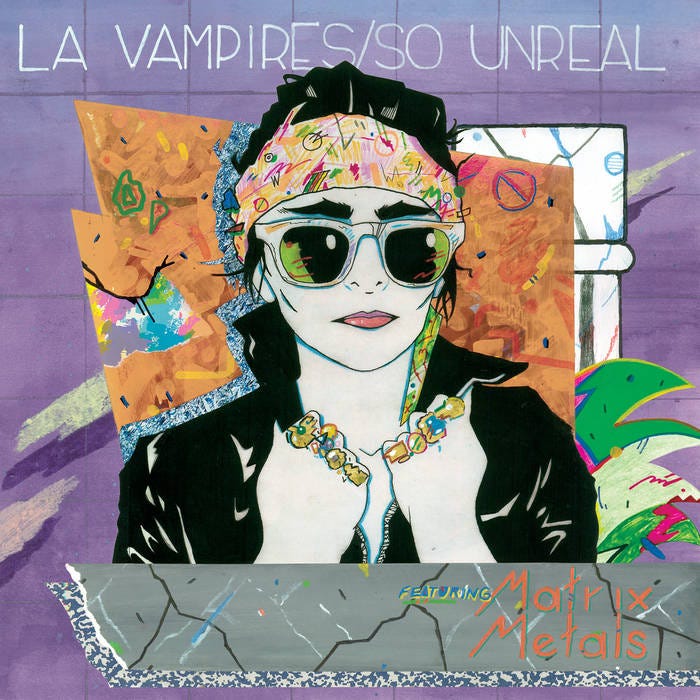

Vaporwave is also a visual aesthetic, created using obsolete digital art and editing software, and this seems to have wider reach than the musical version. I first noticed it when shopping for a second hand record with birthday money in Christchurch. For someone of my modernized tastes, but lack of canonical knowledge, this is a challenging task, and I felt sure I’d come away empty handed, so many choices so little time. But then I saw this LP cover.

Now here, I thought, is some Latina bad girl rock, pop, or hip hop from the late-80’s, early-90’s (I assumed “La Vampires” was a Spanish name). Could be terrible, could be great, would be interesting either way, so I gave it a listen. Imagine my surprise on hearing some very futuristic industrial dub grooves with a breathy Anglo female voice on top from 2010. Exactly the sort of thing I was looking for so hopelessly in the first place!

This house-y 2016 LA Vampires collab with “Melbourne, Australia not-vaporwave electronic producer” Surfing takes us to the not-vaporwave disco. (It’s never a fact until someone denies it).

Researching LA Vampires last year led me to her contemporary Nite Jewel’s ‘Nowhere To Go’ (2013), a perfect post-vaporwave confection that might be chillwave. Note its placement here in the soundtrack to the popular videogame Grand Theft Auto 5. It’s exactly the kind of context a vaporwave artist would be tempted to invent for their work.

Reading Michael Brown’s fascinating book and considering vaporwave as the prime exemplar and ingredient of multiple internet microgenres with similarly nostalgic priorities, I came closer to understanding my reaction to one of the defining recordings of recent internet music, Mona Evie’s ‘Justin Bieber’ (2023). I’ve played this composition to friends who’ve asked me if it’s meant to be ironic, and been lost for words, I mean obviously yes, in a way, but also obviously not, there are wells of sincerity in it, and so BUY NOW’s post-ironic concept suits it perfectly.

Mona Evie’s note to the 2-track single release Jesse, My iPhone White Like Justin Bieber states ”this time we do pluggnb”. Plugg is a dreamy, less bombastic version of trap music that originated on SoundCloud in the mid 2010’s; it is, perhaps, to OG trap what trip hop was to hip hop. Trip trap, if you like. The pluggnb variant adds the melodicism and minor key melancholy of slow jam R&B. But Jesse, My iPhone White Like Justin Bieber’s cover art is undeniably vaporwave in its deliberate use of VHS imperfections, and the vaporwave elements in Pilgrim Raid’s production of ‘Justin Bieber’ are easy to spot - the vast catalogue of old video game and TV cartoon samples that punctuate every second of the song, and the singing monophonic synth preset (I can’t name this instrument, but I’m sure Brown or Rowell could) that weaves through it.4 Also note how the song’s lyric is constructed in large part from aggressive gangsta rap insults, juxtaposed with the explosive gaming effects. If there’s something ironic about Vietnamese artists copying commodified American aggression and flipping it back into the global culture industry, there’s also an affection for all these pop culture elements that transcends irony.

Some vaporwave-styled cover artworks for Mona Evie releases were designed by the second vocalist on ‘Justin Bieber’, Vũ Hà Anh (AKA Aprxel), and the video she directed for ‘Inanna’, a single from her subsequent solo album, the sublime tapetumlucidum<3 (2023), is a masterpiece of vaporwave editing, one that allows us to pick up on all the style’s conventions and retrofuturistic nostalgia intentions. The use of the Vietnamese flag feels as post-ironic as Eyeliner’s commodified track titles (‘Men’s Sneakers’). You can be all-knowing about communism, or capitalism, yet still love your country, or your Adidas.5

The “wave” in vaporwave implies a following that shifts things around a bit, like the wave in yesterday’s tsunami was supposed to do. I was surprised to hear the opening bars of ‘Justin Bieber’ in a new release by VCC Left Hand, who I’d never heard of, with V#.6 The confusingly titled ‘Mình Lượn Lờ Moshi Moshi もしもし’ has a production credit for Pilgrim Raid (as ‘liltrashgod’) and might be an example of something Brown explains in BUY NOW, file sharing and remixing facilitated by Creative Commons licensing. The opening trap beats, monophonic synth, harmonic progression and sound effects belong to ‘Justin Bieber’, while the piano’s tone and notes are different, and a highly processed “shoegaze” guitar part has been added. The rest of the song seems to be a remix of Left Hand’s biggest hit, ‘Mình Lượn Lờ Làm Wen (NOVINA)’, with V#’s vocal added. The wave here is, perhaps, Hanoi’s most experimental pop music making its splash in the Saigon scene.7

When I make a track, using, of necessity, old software like Garageband, I try to create only those sounds that seem “modern” to me. But my idea of what sounds “modern” has been formed by listening to younger musicians nostalgically re-using sounds that I am too old to associate with nostalgia, because electronic sounds have always sounded “modern” to me. I lack a frame of reference in which 90’s futurism can sound retrofuturistic. It’s all accelerationism to me.

Michael Brown’s BUY NOW was, for me, the most exciting read yet in the NZ 33&1/3 series. It tells a story of more general interest than it first appears, is neatly written, full of fascinating facts (Billy Idol on floppy disc!), and minus the usual distractions.

Post-script

If there’s a land without irony, that land might be North Korea. Hayley, brilliant sonic scout that she is, has discovered the synthpop of the DPRK’s top act, Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble. Here’s their ‘Chollima On The Wing’, which, for its first few seconds, reminds me of Nite Jewel.

Algorithmic angst - ‘There is a light that never goes out (synthwave/retro remix)’

Thinking about music as a form of magic, and how everyone goes to Hogwarts these days but Ozzy was turned into a Witch by his own misfortune and that can't be taught. Death to Dumbledore.

Being tactful, like being ironic, is a matter of dressing up what is said, conveying a thought indirectly or by implication, not bluntly and explicitly. In general, ironic utterance forces a gap between the standard meaning of the words used and the particular sense and purpose of their use in context.

Peter Lamarque - ‘Truth and Art in Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince’, 1978

I think we can take it for granted that Yoko Ono’s method excludes irony as far as possible.

On a monophonic keyboard, only one key at a time can be sounded. The earliest synthesizers were monophonic instruments - Switched On Bach and Tomita’s orchestral records were created by a laborious multitracking process.

And yes, that is the deep cut Beach Boys reference you think it is.

V# created my best-of 2024 dance track, ‘Cà Phê Vợt’, in a collaboration with Larria, and this year earns a spot on the playlist with ‘E-Girl’, a witch house collaboration with vsplifff. One of the most appealing and distinguishing features of Vietnamese rap is the highly emotive singing and rapping style of male artists like vsplifff, RAF Kelly, Hồng Phước Văn, and Left Hand.

In December 2024 Vũ Hà Anh released a post-ironic cover of Maria Carey’s ‘All I Want For Christmas’, a song Carey had rerecorded as a duet with Justin Bieber, including some of the sampled effects heard in Mona Evie’s ‘Justin Bieber’, and a section in which her singing is pitch-shifted down into Bieber’s range.

"You can find dozens of successful and well-rewarded guitar acts thriving on the sounds the Sabs created"

Dozens? Hundreds! Thousands! The entire drone metal scene is just playing either Vol 4 or Sabbath Bloody Sabbath on valium, filtered through either "Earth 2" or my fave "Pentastar: In the Style of Demons"... and the sludge scene is the same but swapping out Earth and subbing in Fudge Tunnel. Kick Out The Jams? Shoot 'em up more likely (and we ain't talking firearms).

Vapourwave, and it's rev'd up real high on a ritalin script cousin Hyper-pop are such amazing sonic reflections of the post web2.0 world... https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?&q=GEC+Music&&mid=0A31842DB54EA407D87E0A31842DB54EA407D87E&&FORM=VRDGAR I dig it... but fucked if I understand it at all. First time I felt old. 100 gecs... and tik tok, what the fucks that about??!!!??!

Irony is not involved