It’s said that The Beatles, like the Monkees, were so particularly successful because they combined 4 different archetypes of creativity or entertainment or maleness. The sarcastically funny one, the cute and charming one, the moody and deep one, the clown. There was once a group that combined even more in the way of contrasting talents, although never all at once on record. Soft Machine, before it set out into the world, contained five types – Kevin Ayers, the world-weary troubadour, Robert Wyatt, the extroverted Dadaist, Daevid Allen the psychonaut, Mike Ratledge the polo-necked intellectual, and Hugh Hopper, the mystery man, the inventor, maybe the eminence gris.

We first hear The Soft Machine on a quickly recorded demo recorded by Giorgio Gomelsky, their first manager, and released later, in the budget Faces and Places series, then as Jet Propelled Photographs, to cash in. Not a promising provenance for an album, but because the essence of the Softs was improvisatory it’s a set I’ve always loved. We hear Allen’s often thin and wonky guitar brushing the songs – even when the band had a guitarist, the instrument didn’t take centre stage – Ayers’ rubbery semi-acoustic bass, Ratledge’s weaving, metronomic organ figures, and at this stage the heart of the music is already Wyatt’s virtuoso, jazzy R&B drumming and reedy, non-pop singing about the real problems of his life, at this stage, girls; those he sleeps with, more than those he desires to, distinguishing him from the pop hit songwriters of his times and aligning him with the more adult sexual politics of, say, Dylan, or of John Lennon’s “Girl”.

It's my bed you’re lying on

It's my bed you’re dying on

But if it’s my head you’re relying on

You gotta save yourself

Don't enslave yourself

Just to save yourself

Stay in your own bed at night

Because, girl, you know that if

I try to feed you and keep you all week to make you feel secure

You’ll get overfed and you won't leave my bed

Though you want to stay pure

‘Save Yourself’

The pattern of their music, whether the song is Wyatt’s or Ayers’, is one of tension and release, of power and response, of turning on a dime. Ayer’s songs are more classically psychedelic, formal and complex in their structures – his writing style will be simplified later – and are full of philosophical questions and romantic longing; his deep baritone voice, as a contrast to Wyatt’s contralto, leaves an empty middle in the music which the organ fills.

And, although he isn’t on the recording, we can hear Hopper, because the band is playing his song ‘Memories’, the album’s waltz-time ballad, or bluesy lament.

‘Memories’ had already been recorded by The Wilde Flowers, who included the Softs before they became the Softs; their version is sublime and shows all the band’s promise. It was recorded again by Robert Wyatt on the flip of his Monkees cover, ‘I’m A Believer’ in 1975.

And a gorgeous cover of ‘Memories’ was the first studio recording of a young American, Whitney Houston, singing with bassist Bill Laswell’s band Material with saxophonist Archie Shepp in 1982.

Here’s a duet created after Whitney’s death with Malaysian star Dato' Siti Nurhaliza

Also, in the brief neo-prog era of the early 21st century, ‘Memories’ was covered by Mars Volta.

How did Ms Houston come to record such an obscure British song for her debut? Material (also Gomelsky’s protégés) were US musicians who became Daevid Allen’s New York Gong band, recording the album About Time with him in 1979, and Allen had recorded a version of ‘Memories’ in 1971, with Wyatt singing, for his first solo project Banana Moon.1

Before the recording of the first Soft Machine album, Daevid Allen travelled to France, was busted with pot at customs coming back to Britain (well this is how I remembered the story all these years, but he had simply overstayed his visa), and deported back to France which would become his, and his new band Gong’s, base (Allen was an Australian citizen so had no right of residence in the UK). Soft Machine (a band he had named, with his friend Bill Burrough’s blessing) continued without a guitarist. But there is a later(?) recording of Allen, Wyatt and Ayers together, in a context which explains much about the Softs and the subsequent careers of Hopper, Wyatt and Ayers.

François Bayle was one of those modernist-composer electronica pioneers I mentioned last week, and a creator of musique concrète. He studied with Stockhausen (like Jenny McLeod) and in 1960 joined the Groupe Des Recherches Musicales, an experimental music club founded in 1950 by Pierre Henry (composer of Psyche Rock, the work the Futurama theme is based on) and Pierre Schaeffer. Two of Bayle’s compositions involved the members of Soft Machine.

‘It’ is based around the vocal parts of a song on Soft Machine, ‘We Did It Again’, an experiment in repetition ten years before The Fall’s ‘Repetition’ which shows us that Soft Machine were aware of the NY minimalist school. The sounds that make up Bayle’s larger piece ‘Solitioude’ include police sirens and crowd noises recorded during the May 1968 student riots in Paris, unrecognizable fragments of Frank Zappa and The Mothers’ We’re Only In It For The Money, and a cut-up but recognizable recording of a rock trio’s instrumental jamming. The piece of music they’re jamming on can be recognized as Pink Floyd’s ‘Interstellar Overdrive’, and the players can also be recognized – Robert Wyatt on drums, Kevin Ayers on bass, and Daevid Allen on guitar, taking an unusually lackadaisical approach so probably stoned on Moroccan hash. ‘Solitioude’ even rates a mention in Mark Morris’s indispensable Pimlico Dictionary of 20th Century Composers, where it is described as “a sonic disaster”, helping to explain why I still find it a satisfying listen.

Have you heard of a group called the Velvet Underground? If so, you may know that John Cale worked with minimalist composers in New York and brought those avant garde sensibilities into the group’s sound. The Soft Machine were like that – they were very much the English equivalent of the Velvets, even while remaining as different from them as Canterbury is from New York, and their careers will make more sense seen for a time as Parallel Lives – I’ll be your Plutarch next week, if you like.

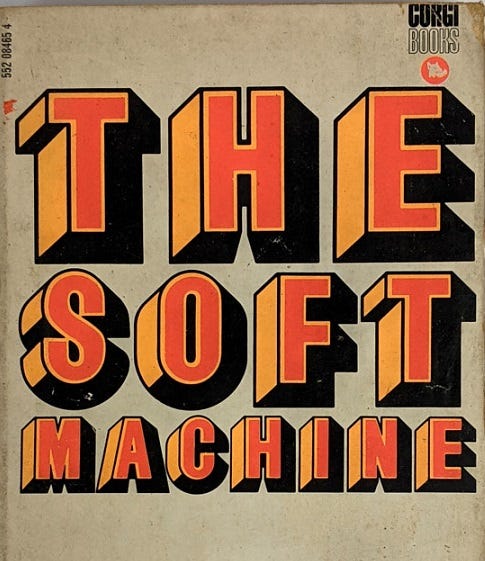

The Soft Machine (the group’s 1st LP) was recorded in New York by Tom Wilson, the producer of the early Velvet Underground, Bob Dylan, and Mothers of Invention albums. A representative compilation of Tom Wilson’s work is the one great work of rock curation that’s still missing in action. At the time, the Softs were on tour with The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Hendrix was not only a fan of the band but had a similar sound at the time thanks to the jazz feel of his UK rhythm section. It’s said that Wyatt sang backing vocals on ‘Stars That Play With Laughing Sam’s Dice’. The US tour was grueling and too much for Ayers, who quit the band to be replaced by Hugh Hopper. Wyatt and Ratledge do however play on some of Ayers’ subsequent solo material (as well as on Syd Barret’s The Madcap Laughs) and songs like ‘Soon, Soon, Soon’ and the ‘Song For Insane Times’ that gives this blog its name are arguably that first Softs lineup’s best recordings of Kevin Ayers songs.

Volume Two, with Hugh Hopper on the nicely fuzzed-up bass that would be his trademark, is the high water mark of Soft Machine as a rock group. The songs square the circle between jazz-prog rock and R&B in a way that no-one else has ever managed; they are complex, often oddly time-signatured, yet catchy, cute and sexy.

Virgins are boring

They should be grateful for the things they're ignoring

Why be smug about the time wasted

Time that could be spent completely nude, bare, naked

‘Pig’

Side 1 is ‘Rivmic Melodies’, a 17 minute medley which is mostly Wyatt’s arrangement of several of Hopper’s melodic and lyrical ideas, beginning with Wyatt’s ‘Pataphysical Introduction’, and ending with the band’s shout out to their friends, including Jim(i) and his manager Mike Jeffery, surely the only time Jeffery, whose controversial relationship with Hendrix deserves to be the subject of a movie, has been mentioned in song.2

On side two, there’s a song about the missing Ayers, ‘As Long as He Lies Perfectly Still’, a little art song by Hugh Hopper, ‘Dedicated To You But You Weren’t Listening’, picked on an acoustic guitar, and a suite of Ratledge’s composition, ‘Esther’s Nose Job’. If Volume Two has any fault it’s that Ratledge has uncharacteristically chosen to use a piano instead of his organ for much of it and the tricky-to-record instrument bleeds all over the place and muddies the sound, a problem rectified in the live recording of the Volume Two set from this period later released on disc one of Kings Of Canterbury. This live recording confronts us with the shocking truth that Soft Machine at this time were the Best Band In The World, playing with such supple power and originality, such loose perfection, that it doesn’t matter that Wyatt is shredding his vocals into unintelligible squeals – this was a rock group.

While in the USA in 1968 Robert Wyatt recorded a set of demos for a long song which would become the stand-out track on Soft Machine’s Third, ‘The Moon In June’. The title’s mockery of facile Tin Pan Alley rhyming romances is an example of Wyatt’s typically self-deprecating approach to the creation of love songs, supposedly an embarrassing and uncool occupation for a serious musician, and certainly a tricky one, and also serves as a deflationary reference to the value of “love” within the song’s lyric, as it fluctuates according to the effect of distance and homesickness on competing affections:

You can almost see her eyes, is it me she despises or you?

You're awfully nice to me and I'm sure you can see what her game is

She sees you in her place, just as if it's a race

And you're winning, and you're winning

She just can't understand that for me everything's just beginning

Until I get more homesick

So before this feeling dies, remember how distance tells us lies

‘Moon In June’ ends with a non-sequitur, two quotations from Kevin Ayers songs; the players of Soft Machine remained friends, and showed their regard for each other in song when apart. Third was the last Soft Machine album with vocals; Fourth would be the last with Wyatt on drums, as the world’s once-greatest rock band slipped noodlingly into jazz-fusion mode.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

It seems to have become a theme of these writings that I’m finding music most meaningful when it introduces futurity; new ways of thinking, new ways of combining sounds, new technologies, etc. Or rather, when it does this with heart, for which intelligence is no substitute. Jazz-rock fusion music is an example of something that was futuristic at the time it was invented, but that had such a great capacity to remain static that it may as well have been reactionary, with a few exceptions like Joni Mitchell’s 70’s work and Robert Wyatt’s work with Matching Mole, which we’ll look at next week as we consider the original Soft Machine members’ solo projects. What those exceptions have in common is a great lyricist who needed the music to evolve with the expression of their feelings and ideas.

Algorivmic nudge - The Clientele’s ‘The Garden At Night’, which reminded me of the Soft’s ‘We Did It Again’ when I heard them play it at The King’s Arms in 2007, a song The Clientele assured me they’d never heard. Great minds…

Banana Moon also featured Gary Wright of Spooky Tooth, an English group who had worked with Pierre Henry on his album Ceremony - An Electronic Mass, which at record company insistence was released as a Spooky Tooth album and destroyed the band’s career, a decision described by Jim Farber as "one of the great screw-ups in rock history". With hindsight, Henry’s electronic and musique concrète interference serves to redeem Spooky Tooth’s painfully bluesy sound, but that sound was popular in its day and Ceremony must have seemed sacrilegious to their denim-clad acolytes.

Charles Cross’ Hendrix biography Roomful Of Mirrors, a well-researched book albeit written in an unfortunate journalese style, tells us that Jimi and Mike took acid together.

me & sean o'reilly once (about 1999 i suppose) recorded a "cover version" of the françois bayle piece you mention in this essay

you'd probably have to know the original extremely well to recognise what we are trying to replicate tho

tape still exists somewhere i think tho i seem to remember sean telling me the original 4 track reel broke & he had to splice it with sellotape